| |

|

publication | Big Red & Shiny

date | August 2006

writer | Avantika Bawa

website | bigredandshiny.com

|

GREY|AREA @ GUESTROOM GALLERY, PORTLAND, OR

by AVANTIKA BAWA

grey|area, curated by TJ Norris at the Guestroom Gallery in Portland, Oregon is an aptly titled show, which exhibits the work of thirteen West Coast artists. The works in the show include a range of media that either deliberately or unknowingly resist immediate and easy categorization. Instead they confidently straddle established genres, revealing in the process the scope of overlapping territories. By drawing attention to serendipitous details, a tactile minimalism and the often unseen, this overlapped grey area becomes a huge platform that initiates thought and provokes debate. What is it that makes this overlapped space -- this blur -- a space worthy of exploration?

At first glance the works emit different auras that create a visual fragmentation; what holds them together in this already fragmented space is the use of grey in all of the works and the inclusion of color to create the chromatic grey of the walls. The mild pulsation between the chromatic and achromatic greys emitted by the gallery space and the works it features generates a positive energy, allowing for a fluid and engaging navigation between the (un) conscious states of mind/being as intended by the curator in his statement. Bringing to mind Johannes Itten and his theories on the Contrast of Saturation this pulsation also adds a subtle yet desirable tension.

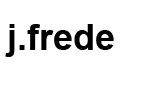

The works that speak immediately (in part due to their sheer mass and odd shape) were Alert by Los Angeles artist sound sculptor j.frede, Postscript (T.W, L.C., N.S, A.M., L.C., D.B.) by Portland-based sculptor and performance artist David Eckard and Nest by Daniel Barron from Olympia, WA. Alert by j.frede creates cold synaesthetic experiences of sight, sound and touch that are unusual and strangely reminiscent of cold war hysteria. If one were to imagine a piece of post war minimalist art with an industrial tone, it may resemble this formally tight work. Consisting of a white box and a steel grey megaphone, it sits on an unassuming white pedestal but when the red button on it is triggered, it lets off an endless drone that builds up in pitch and harmony as seconds pass. Who was it alerting and what is its message? The absence of a clear-cut audience or message adds an ominous mystery reminding its engager to fear the unknown.

Eckerd’s investigation of endurance, duration and randomness through his piece Postscript (T.W, L.C., N.S, A.M., L.C., D.B.) creates not only a beautiful sculpture but interesting drawings as well. It includes a spherical glass container with an unlit wick to which is attached a framing device that holds a panel of board. It is apparent that the smoke of this apparatus when lit creates the ethereal marks on the additional panels that are elegantly displayed besides it. The work draws attention to a mysterious experimental mark-making process that embraces the futile thereby allowing chance to take over control. It would be interesting to see either the performance itself or evidence of it. In its current state it resembles an archaic piece one might see at a museum of unworkable devices. Maybe then, this enigma is a good thing?

While the aforementioned works walk the more sculptural and performative, conceptual and political lines of the show, the paintings in grey|area lean more obviously towards a singular medium, immersing themselves in the identifiable (but not necessarily easy) realm of abstraction. Abi Spring’s heavily layered blue silica monochromatic work, White Peace comes across as a contemporary and painterly equivalent of Rauschenberg’s Erased DeKooning. There is strength in the visual refrain of a complexity created through the use of monochrome blue and heavy sanding. Hers is the only work hung in front of a white wall, a sensible decision given the vast blueness of the piece that would be significantly altered with any color behind it.

The Liz Taylor Piece - a book on the actress with pages that are aggressively collaged by multimedia, guerilla-style artist Scott Wayne Indiana, has some interesting components but is too overwrought and literal making it an odd bird in a show with quieter and greyer tone. Flipping through this book and then looking at his painting The Diamond Cutter that hangs nearby, makes the painting appear as a pleasant and well-behaved version of the ideas attempted in the book. The passive aggressive veiled layers of tinted and desaturated hues add to a subliminal mystery. Distancing the book from this work would give it an even stronger presence.

Much like the paintings, the photographs in the show share a similar affinity towards abstraction. In these one can notice an obvious and noteworthy dialogue on organic and geometric references. The organic oddity in the photographs by Chris Komater, Daniel Barron and Jamie Drouin create a surreal yet conceptual experience that draws attention to crossovers in the realm of film and digital media. These crossovers would resemble works by artists such as Mariko Mori, Luis Bunel and Dizga Vertov if one could visualize them morphed.

TJ Norris’ photographs on the other hand initiate thought of geometric abstraction. His diptych, (untitled) grey|area. includes the image of an uneven grid of partially chipped white cement blocks and to the left of the diptych are white squareish abstract marks of a similar size to the blocks. This photograph is formally tight and by echoing itself it becomes curious and clever. Perhaps it needs to be larger and left alone on its wall, sans the other work, (untitled) signs. Several of the other 2D works in the show felt a bit too didactic and trapped in tradition and unfortunately offered nothing new or risky to a curious viewer. Their obviousness along with the narratives they evoke appear a little disparate from the satisfying ambiguity and grayness of the works.

The subtlety and honest simplicity in the delicate works of Laura Fritz, Ty Ennis and Ellen George provides an effervescence that encourages the viewer to pause and ponder. In Laura Fritz’s Illuminant, the controlled incidentals of production such as pours, spills and ripples work successfully to create a curiosity and inspire feelings of attraction and unease, as stated by the artist in her statement. The looseness and randomness created by a spill of some sort of polymer and the industrial stand on which it rests draws attention to the odd juxtaposition of the object and the stand itself. What is it that is controlled, the stand or the spill? Does it even matter?

Control again is consciously executed in the delicate line work of Ty Ennis’ commendable ink drawings that speak of a hand that knows how to resist. These ink portraits boldly linger on the boundary of the finished vs. unfinished, adding an appealing freshness to them. The questionable degree to which the three pieces on display are linked prompt the viewer to consider whether the pieces would be better served by either extreme-much more or far less a divide.

With Ellen George’s Little City, one is reminded of the sweetness a precious work of craft can elude. It has a magical quality and appears to be conjured out of strands of the clay that now forms the topography of a ghost town with mass and an acknowledgeable presence. Some of the recent works by the artist at her solo show at PDX Contemporary came close to seeming too crafty and formulaic. Perhaps the absence of color and the solitude of Still enabled it to stay away from the same accusations in this show.

On the whole the show is cohesive, and the candor and the boldness with which the curator trespasses areas of blur to accommodate the work of thirteen varied artist quite impressive. With the excessiveness of the art market/world today and its tendency to constantly categorize, subcategorize and pigeonhole, a show that blurs boundaries and addresses the plentiful in a state of nothing is refreshing.

|

|

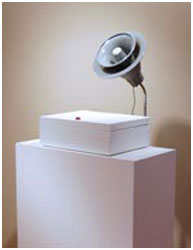

publication | Signal To Noise Magazine

date | September 2004

writer | TJ. Norris

website | signaltonoisemagazine.com

|

The Aural Organics of j.frede

By TJ. NORRIS

In the last half dozen years j.frede (born James Frederick in New Mexico, circa 1975) has slowly emerged in the City of Angels as one of the world’s premiere young phonographers. His work embodies the presence of the ethereal in works that fluidly blend organic field recordings with bold digital technologies. Frede’s intuitive compositions source sounds from his immediate and distant axis having actively explored the subtle tones of field recordings in his compositions since his first European tour in 1998. In a constant process of discovering what he explains as “countless natural sonics” the environment often brings him all the acoustics he requires that do not exist in the synthetic or digital realm. He sees himself as an integral part of a burgeoning community of phonograhers that includes such other notable artists as Seth Nehil, Christopher DeLaurenti, MNortham, Dale Lloyd and Eric La Casa among many others. You can surf to www.phonography.org for the latest in who is currently channeling the elements. Labels like 12K, Accretions, and/OAR and Intransitive have supported the emergence of sounds bathed in the cryptic harmonies between nature and man. When I spoke with frede from his studio in Los Angeles he said “Recently I have been doing contact recordings of trees and plants for an upcoming event in LA that will focus on sounds from nature.” From bees and trees to flowers and showers, frede’s insistent passion for bringing aural harmony to spaces with more super highways and stripmalls than a bit of green may make him the Henry David Thoreau of his generation.

Most recently his work has become something of an excerpted, accented, and it might even be called post-self, collaborative work with UK’s Scanner (Robin Rimbaud). On ‘j.frede Rewrites Scanner’s Diary’ the latest recording which is now available on frede’s own Current Recordings (www.current-recordings.com) he takes on Scanner’s Y2K ‘Diary’ CD release, a live recording, as the source material for a completely re-scripted interpolation of the original, based on Rimbaud’s daily journal dated back to the Disco era (1976). This somewhat traditional process must certainly pose a challenge for an artist who seems to only be constantly traveling the globe. Frede says “I was visiting Robin in London at the end of 2001 and he gave me a copy of his ‘Diary’ CD and he explained about the accompanying tour and his personal discipline with his diaries. I loved the concept and the recordings that went along with this album so in 2003 as we were discussing collaborative projects we both felt this would be interesting and thought the title was rather funny....so it began.” As electronic music can often be interpreted as impersonal, frede’s use of such private and nuanced artifacts of memory truly counters the ultimate means to an end herein. As the recording plays, the pages of Rimbaud’s personal passages unfurl under the mysterious, stop-start harmonic convergence frede composes. “I began taking apart his live recordings from the CD, taking care to not mix the sources from track to track, out of my own neurotic conceptual nature, and create new tracks or in this instance "pages" from the recordings. The finished piece is a full length album that explores Scanner’s textures and sounds arranged in new compositions.” Quiet, dreamy isolation meets fragmented memory bits head on.

And Rimbaud is not frede’s only collaborator of late, he is what some may call a co-op artist, merging his mind and talent with many others who lay the land high and low including professional piano tuner David Nereson on frede’s recent “Unprepared Piano” release (Current Recordings), his noise work with a hardcore band named Deadlock Frequency, and other unreleased work projects with veteran sound artists Kim Cascone and Francisco Lopez. He shyly admits that there are other collaborative projects on the horizon that “i will keep quiet for now...” His collaborations grow from friendships and through various correspondence.

As a visual artist frede has developed a growing roster of ongoing installation pieces. With a small band of artists who work in this modality, his combination of sound with sculptural elements, video and other interactive technologies takes an avenue that enables the audience to have a more full experience of the sound center of the work. Each of his sound sculptures follow a strict conceptual format, that aligns to strict disciplines in his life and for years he was plain bored of simply performing live in the typical stereo PA construct, so he incorporated working with live quadraphonic performances that leant to the experience of site specific sound space. This, of course, set up a precedent for challenging the average audience’s attention span, and those who typically come out to a show for flashy bling-bling would be in for a completely different mind altering body numbing experience at the helm of frede’s craft. When asked if he could reflect on his process and discuss the temporary nature of creating work in a more physical context, effecting how the visuals or sound might come first he explained “Each installation varies - some are for single evening engagements some are long running exhibitions. I have found it easier for people to relate to my work through my installations than through my live performances - people have the option of understanding it at their own pace, and they are not forced in a seat for 20 minutes... so as much as I love performing live, i am very passionate about presenting installations.” His methodical approach is readily identified as he went further saying “My process..... well I have a book full of "future works" that I keep, when an idea or a concept comes to me I sketch down all of the info onto index cards then organize the ramblings and type them onto a "projects" template - then I print them out and file them into the future works book.”

From museums and planetariums to Nazi bunkers (Blockhaus in Nantes, France) and on the hull of a ship the live experience in frede’s world is more of a basic shifting of the alchemies of sacred turf. Performing live allows him the ability to really focus on the sounds available at the speed of real time. He releases binaural sounds captured in his travels throughout Europe and the United States into foreign and contained live spaces where the dynamics of the particular piece and the duration of the performance may vary depending on the performance environment. He weaves sound textures creating real-time spatial environments that move what you hear around the space manually or by sequencing the pans.

Get something on your chest! This Summer frede introduced a vibrant new series of t-shirts called “current.array” created to bring print designs from composers working in the field of microsound and lowercase music. The artists include Janek Schaefer (AudiOh!) who’s “12 Tone Turntable” is something of a dizzying vortex for turntablists with a passion for lock grooves and scratching, the contained dna of what could be the origination of tie-die in “Voice Print” by Steve Roden (Trente Oiseaux, Sirr) and John Hudak’s (Alluvial, Intransitive) swirly James Bond meets Vertigo-a-go-go.

In 2003 frede birthed the LA-based imprint Current Recordings, his second record label. Passion intact his penchant for producing work got him into curating sound festivals and events that initially helped launch his first record label, Ritual Document Release. The handprinted, handmade design and packaging is an fundamental part of the label, providing a more elegant, human touch to the standard jewel case packaging process. And the future is bright for Current, as they are currently putting together the Fall release from LA-based composer Kadet titled "Thin Air" as an enhanced CD with a 3D interactive application "Sensorium" created by Kadet and Reto Schmid. Other future releases include a 3" CD from David Brady and a limited 7" from Steve Roden. As artist, curator and label chief, frede is working harder than ever to establish new ways to morph art forms and genres melding the creative stylus, not slowing down for a nanosecond on his electronic freeway.

|

|

publication | Westword

date | November 2003

writer | Jason Heller

website | Westword.com |

Wired

Science

From

laptops to insects to wineglasses, j.frede's sonic experiments

leave no sound untweaked.

BY

JASON HELLER

I never saw any relation between my upbringing and the

art that I do," says j.frede, the former Denver aesthetic

agitator who now resides in Los Angeles, where he has been

making a name for himself as a composer and performer of

experimental music over the past two years. "I grew up in

southern New Mexico, in Hobbs, a really small cowtown close

to the borders of Texas and Mexico. Recently I went back

home, and as I was pulling into town early in the morning,

I realized that my entire surroundings for the first fifteen

years of my life were just the most strict minimalism you

can imagine. It's the Great Plains; you spin a 360 and there's

little to no trees, no mountains. It's just solid horizon.

"It hit me like a ton of bricks," he goes on. "I realized

what a lasting impact that environment had on the sound

that I do, that I'm attracted to. It's always been really

stripped-down stuff."

Born James Frederick, the 28-year-old artist abbreviates

his music as radically as he does his name. Like a sculptor

who sees the statue at the middle of a block of marble,

he's been unflinchingly chiseling away at his musical vision

over the course of thirteen years and nearly thirty releases.

And now, with two brand-new CDs and a series of ambitious

performances showcasing his conceptual minimalist technique,

j.frede is finally hitting his core.

Frede's first experience playing music was at age fifteen,

when he was the bassist of a goth band in Albuquerque. He

soon dropped out of school, however, and wound up homeless,

hopping trains and living on the streets of L.A. and Texas.

And although many troubled street kids wind up drunk or

strung out, frede has been straight-edge -- drug- and alcohol-free

-- his whole life. "It's not better or worse," he says of

his abstinent philosophy, one codified by '80s hardcore

punk bands like Minor Threat and Youth of Today. "It's just

a different choice. I had already made that decision before

I found out what straight-edge was, when my older brother

turned me on to Minor Threat."

In 1995, after frede settled in Denver, he started Halopane,

a band that, though derived from goth, favored a stronger

experimental approach. As he remembers: "Halopane had two

basses, a drum machine and some weird tape loops. We were

completely unaccepted by the goth scene, ostracized by all

the goth kids who just wanted to hear typical death-rock

stuff.

"All my sounds have always been of a darker tone, just

not in a ŒScary Sounds of Halloween' kind of way,"

he continues with a laugh. "Not cheesy, but more like old-school,

early horror-movie soundtracks."

During a year-long sojourn in San Francisco, frede immersed

himself in the mystical, almost psychedelic drones of Sleep

Chamber and Psychic TV, both of which inspired him to form

two major vessels for his creative restlessness: the music

project Chapter 23 and the record label Ritual Document

Release. Upon returning to Denver, he began playing live

and putting out limited-edition cassettes dressed in elaborate,

handmade packaging -- displaying his knack for graphic design,

a preoccupation he believes correlates directly to his music.

"A lot of the noise stuff that I was getting into at the

time came in special packaging, and it really floored me,"

frede remembers. "It just seems so much more appropriate

for this type of music to be presented in a non-traditional

way. I would do an edition of 25 tapes, and every tape would

have different music on it and would be hand-painted, with

no labels. I would just give them out to people." He soon

moved on to even more involved packaging that incorporated

silk-screened fabrics, stitching, Army-surplus materials

and even white decal letters painstakingly arranged on blank

LP sleeves.

As the wrapping around frede's releases grew more sophisticated,

so did the sounds inside. Generated at first by cassette-tape

loops ("Because of a lack of funds, I couldn't afford equipment

or samplers," frede remarks), Chapter 23's music was mantra-like

yet abrasive, an instrumental mélange of jagged noise and

jaw-snapping static reminiscent of the more abstract work

of Merzbow or Einstürzende Neubauten. But as he built up

an arsenal of hardware, frede's output ironically became

more minimal. He began enveloping his harsh electronics

in arctic washes of ambience, conjuring a bleak, hypnotic

soundscape that owed a debt to twentieth-century avant-garde

luminaries like Terry Riley, LaMont Young and Brian Eno

as much as the post-shoegazer narcosis of Main and Flying

Saucer Attack.

But frede's turn from chaos to tranquility was simply an

outgrowth of his own character rather than a conscious stylistic

decision. As he explains, "I'm really not interested in

being very demanding or like, ŒLook at me! Look at me!'

If you get what I do, okay, that's great, but I'm not going

to shove it down your throat. I like using a more subtle

approach to presenting something. I was never very interested

in the idea of demanding people's attention."

The subtlety of frede's approach became even more apparent

with his discovery of field recordings -- the process of

capturing and manipulating environmental sounds that was

pioneered by composers like John Cage and David Dunn. "I've

done just about every field recording you could imagine

at this point," he says. "I've been interested in lots of

field recordings that actually sound synthetic. If I can

find natural sonic atmospheres that sound like something

someone created with a synthesizer or software, that's what

I'm really drawn to. For instance, I did recordings in my

parents' windmill, down inside the pipe. It creates this

unbelievable effect that sounds like a really heavy, rich,

gritty chorus. I also did a recording of desert insects

out in the middle of nowhere on the drive between Los Angeles

and New Mexico. I had to pull over; it sounded just like

an electronic buzz everywhere.

"And this last summer," he adds, "I recorded in Utah at

this hotel that I had stopped at. The sky was full of bats,

and it sounded like wires buzzing or something, this thick

blanket of bats eating insects above me."

His obsession with field recordings led frede to embark

on the Audio Journal Tour across Europe during the winter

of 1998. Throughout Finland, Sweden, Norway and Germany,

he set up microphones in each city and used the resultant

snippets of background noise as sources for that particular

evening's show. By sampling, looping and processing these

sounds, his performances became intimately unique to each

setting, as well as displaying a sympathy and sensitivity

to the surrounding culture.

"The thing that really stood out to me in Europe was all

the language," he elaborates. "I would record lots of conversations

and bus announcements and train announcements. And who knows?

When I played to people in Finland, maybe they were like,

ŒWow, this guy's making sounds out of someone reading their

grocery list.'"

Still, as frede describes it, the European tour was "very

hard, almost crippling," and he aborted the mission after

four weeks rife with poor turnouts and non-paying promoters.

On the long plane ride home, bursting with inspiration from

the small yet cohesive experimental scene he witnessed in

Scandinavia, he outlined his designs for Denver. In February

1999, just three months after returning to town, he opened

Chernobyl, a Capitol Hill art space that served as a venue

for touring noise and experimental acts and exhibited multimedia

works coupling audio and visual elements. After Chernobyl

closed a few months later, frede refocused his attention

on the Atonal Festival, an annual event he created years

prior that brought together many local and national figures

from the world of contemporary avant-garde music. The final

Atonal Festival, in 2001, was a massive two-night affair

at the Gothic Theatre, during which the venerable hall was

transformed into a labyrinth of textures, oscillations and

bit-mapped rhythms. Among the laptop-and-synthesizer set

was Kim Cascone, just one of the many acclaimed, internationally

known artists with whom frede has associated and appeared

over the years. That roster also includes Kit Clayton, Francisco

Lopez, Robin Rimbaud of Scanner and Sonic Boom of Spacemen

3.

Frede and Cascone have a split release due next spring,

but frede's most recent collaboration is with Denver pianist

David Nereson. Dubbed Unprepared Piano, the disc

is an exploration of mood and void in which frede uses editing

programs to tweak, modulate, layer and arrange dissonant

samples of an antique upright piano being tuned. His other

new release, though, is even more noteworthy. Produced in

partnership with IDM artist Carlos Archuleta, BLIP: The

Glitch Electronica Standard Reference was put out this

summer on the Sonic Foundry imprint, a subsidiary of Sony

that specializes in providing raw material for musicians

and producers to utilize, copyright-free.

Archuleta is also frede's partner at his record label (now

called Current Recordings in honor of the gradual shift

in focus from the Ritual Document days) and is slated to

participate in frede's newest live undertaking, Glass

Music. This one-time performance will take place at

Denver's Museum of Contemporary Art, where frede appeared

often before moving to L.A. in 2001. Almost a rebellion

against his usual computer-based compositions, Glass

Music is a symphony of struck wineglasses during which

approximately eight players -- including Archuleta, electronic

musician Marleah Tobin, professional composer Mark McCoin,

ex-Blue Ontario bassist John Parks and frede himself --

will encircle the audience while coaxing euphony from their

rather unorthodox instruments.

"I got the idea from doing the dishes," says frede without

a trace of sarcasm. "The sound of glass is completely natural

and acoustic, just the purest sound ever. There will be

two parts of the performance: The first will be a duet between

myself and Marleah using wineglasses to generate a drone

piece out of the tones and resonance of the glass. And then

the second piece will be with the whole group, half improv

and half arranged by myself."

Besides preparing for Glass Music and his visit

to Denver, frede remains dizzyingly busy. Between showing

sound installations in galleries from L.A. to Portland,

readying a second volume of BLIP for Sony and recording

pieces derived mathematically from the patterns of pixels

in digital photographs of buildings, the tireless artist

has five complete albums in the can and awaiting release.

But amid all the plans for more world touring and prestigious

festival appearances, the lure of the dusty desert plains

of frede's youth still beckons.

"It's so much more removed out there than it is in the

city," he explains. "There's so little noise pollution in

the desert or rural environments. You can really capture

the natural acoustics of a landscape as opposed to a lot

of noise from civilization. Actually, Marleah and I are

going to be doing a project sometime in the next year documenting

the entire American West with photographs and field recordings.

"You know," he adds with a hint of reverence in his voice,

"that whole isolation of the American West."

With frede's effusive passion and ambition, it's doubtful

his chemistry of high concept and stark beauty will stay

isolated for long.

|

| |

|

publication | LA Weekly

date | September 27th 2002

writer | Greg Burk

website | laweekly.com |

Sound for Sound's Sake

This, too, is music

Some music, you just wonder where it came from. Maybe you like it, maybe not, but you can tell right away that its maker wasn’t trying to make you dance, hum, worship or vote, wasn’t decorating anything, and wasn’t expecting money, fame or sweetsweet lovin’. Now that anyone who can buy a car can buy a computer, and cheap electronics have made it possible to change the sound and image of anything into anything else, more humans are turning ears toward decades of preceding scrapes and howls barely heard from within the deep woods of theory and practice, to rethink what music can be.

So: a greater amount of music without notes or chords, often without rhythms. Drones, loops, noises. Music flowering through unusual processes of thought, and through processing existing sounds.

I gnawed on the notion of process. And while asking a bunch of such mostly local sound makers if they’d type a few words about what they do, I also asked them if process music might be a good term to describe it. Process has been used by various explorers in different contexts at least since the ’60s; some respondents liked it, most didn’t (too cold, too much baggage), but many felt that some term might help draw listeners to what still tends to be perceived as weird, and not weird in a good way. Almost nobody liked the battered and stretched terms that have been floating around, such as sound art, experimental/electronic, lowercase and glitch.

These artists use all kinds of sound sources (light bulbs, water, toys, field recordings) and equipment (effects boxes, contact microphones, samplers, sonification software). Their music ranges all the way from meditative beauty to obnoxious eruption. And you can hear them in small L.A. venues most every week. I asked them what they do, and how and why they do it.

What

Rick Potts (Solid Eye): Sounds alone can create feelings and thoughts, and bring ideas and memories to the surface.

Mark Trayle: John Cage had a huge influence on me. The idea that sounds could be sounds, that you didn’t have to spew your ego and emotions over the five-line staff, was incredibly profound.

Loren Chasse: I am very interested in how listening becomes a creative act. In teaching sound art to children, I realize how significant it is when a child first hears the world amplified through headphones. Another important element is physicality — I like my work to somehow attach itself to the body, to have something in it that is

biological.

Glenn Bach: My artistic process is rooted in an embrace of Zen sensibilities, particularly the aesthetic of wabi-sabi, in which beauty is found in hidden details, the evolving/devolving of things, and the impermanence of matter — ideas that are perfectly suited for sounds that arrive and then fade into silence.

Civyiu Kkliu: It is a distraction from the work to write about or discuss its making. Too often questions of methods and process supervene on art, especially sound art, like typhus on a gunshot wound — and the interestingness of the making affords, synecdochically, interestingness to what’s been made.

Matthew O’Donnell: You will never find me with a guitar in hand and 10 pedals at my feet. The artist who takes this approach has left the thinking up to Guitar Center. I’m working on a conceptual level. I recently was invited to a local college radio station (KSPC) to play some of my field recordings, and a listener called in to see if the station was "broken." I was flattered.

Albert Ortega: I assemble gadgets in hopes that this system will reveal a simpler, broader definition of music.

How

Leticia Castaneda: I use the studio as my instrument, so the process is not only hands-on work, but it also savors and boils in my mind day and night.

Steve Roden: Sometimes I use real instruments, such as a lap steel guitar, which I don’t know how to play properly; this can lead me to discover new sounds or performing patterns. With field recordings and objects, I am interested in transforming the outward characteristics of these things — yet their integrity remains intact; the place or the object is still beneath the surface of what you are hearing.

J. Frede: I just finished recording and filming at the windmills in Palm Springs — all together, they create amazing sounds. Or you can take a recording of any street and play it back in a different environment and hear lots of sounds that you never would notice.

Jerry Lloyd (Feverdreams): I have a computer full of stuff that may have started as a metal pole contact-miked and effected, or a guitar, played with a chisel, that has been slowed down three octaves, stretched out to reveal new sounds, effected further, bent into itself to form strange "chords," etc. I am sometimes asked, "What’s that?" about a particular sound on a recording of mine, and although the sound is my own, I have to reply, "I don’t know."

David Cotner: If I were to compose a piece based on cold, then the rhythm track might be a circulating fan, ice, the field recordings of my trembling hands, and low bass frequencies that, when pumped through a set of speakers, create wind, which is the nearest I’ve been able to get to actualizing an idea as a physical entity.

Glenn Bach: As a visual artist and poet with no musical training, I discovered digital noise as a tool with which to access the insider world of music making. Most of the initial sound sources I use come from photographs I have taken of the urban landscape. After scanning the pictures, I sonify them through bitmap-to-wave converters. I then highlight silent gaps between sounds, magnify and process the latent noises buried there, discover patterns and drones in these interstices, and introduce these new constructions into multilayered compositions. Often I will convert these new sounds back to images, then repeat the process all over again.

Bob Bellerue (Halfnormal): I create sound objects out of various materials, including those used in the construction of homes and representing consumer safety and security (glass, metal, wood, etc.).

Matthew O’Donnell: I build my own instruments and usually refer to them as "systems" since they are self-contained and autonomous. I set up a system — i.e., arrange boundary conditions or create a physical situation — and let nature do the rest, as Alvin Lucier did in so many of his works.

Albert Ortega: My music explores the physical effects of sound as perceived by an Acoustic Operating System (AOS) that listens, memorizes and responds to its immediate surroundings (trees, a windy tunnel, a small room). An AOS is a very primitive, self-operating, real-time sampler/monitor that manipulates the sound source using various resonant objects (cans, snare wire, gourds) rather than multi-effects units to produce what I call mimetic music.

Pete Martin (Eddie the Rat): I perform/compose through a 13-piece ensemble of musicans/"manipulators" and "voice-people"; it has been called a noise-jazz-avant-garde radio-drama-in-progress. We employ cyclical patterns juxtaposed against each other in musical arrangements. It started as me in my room with electronic stuff. But when you get 13 to 17 real people, you get structure plus a bona fide emotional-musical reaction to it.

Josh Russell: It would be great if a performance space could open up where there is no street noise, a high-powered PA with subwoofer, and lots of futons and cushions for people to relax on.

Why

Leticia Castaneda: This music is the most honest approach to express the confusion and peace that I recognize.

Steve Roden: All of my work comes from a need for some kind of exploration. My approach has always been that it must be honest and come from a simple activity like picking up two stones and clicking them together. Sometimes I sing (which led a German concertgoer to tell me he loved everything except my voice, which sounded too much like music).

Brian Williams (Lustmord): Hell, I started because nobody else was doing what I wanted to hear; now I do it because it’s what I do/who I am. I also do it as something of a day job for film and video games.

Bob Bellerue (Halfnormal): The sound-art scene has the complex visceral beauty that I’m looking for and, to top it off, is lacking in at least some of the competition and ego trips of the rest of the music scene.

Loren Chasse: Being a big nature freak, I found myself less and less interested in working in-studio and more excited about making "studios" wherever I went.

Mark Trayle: It’s what I like to listen to. I somehow got bumped off the pop-music mainline in high school and headed for the most extreme thing possible.

David Cotner: It interests me, and being interested in something — that situation — is what fuels more action in this world than boring old hate, love, vengeance, sex, etc.

Civyiu Kkliu: It doesn’t entertain me. It is strong, flat and indifferent like objects — objects that are aesthetic - ally rich.

Pete Martin (Eddie the Rat): It has kept me awake for years.

Don Bolles (Kitten Sparkles): ’Cause it’s easy. If something involves any amount of difficulty, it’s not my music.

Josh Russell: Initially I tried to make other types, but had no patience and talent for it, so I just started to hone what comes to me naturally.

Rick Potts: It feels good. It’s transcendent.

Daedelus Darling: Can’t really help it. |

|

|

publication | Go-Go Magazine

date | July 2000

writer | Jason Tyson

website | gogomagazine.com |

taken from "3 DJs - The Evolution of the New Musician"

THE GUERILLA ABDUCTOR J. FREDE DOESN'T MAKE MUSIC, HE REGURGITATES SOUND

Guys like j. frede make me feel old and out of touch at 25. When I told my mother I was going to watch a local DJ play for a story I was working on, she asked me which radio station he worked for. I scoffed then, but later that night, watching j. frede perform at The Mercury Café on what looked like nothing more than a laptop, a mouse, and a shoebox-sized soundboard, I was the dinosaur. Where were the upside-down visor, the glowsticks, the turntables, and the crate of records? What the fuck? Turns out the 26 year old isn't really a DJ after all, he's a "sound abductor." He abducts sounds he hears all over the place-- from a Speak-n-Spell he rewired, to the noise of traffic outside, to the clatter in his kitchen. He records these sounds and turns them into electronic soundscapes using a computer and assorted synthesizer equipment.

Without telling anyone in the crowd, he abducted the Denver Gentlemen at the Mercury Café that night. Not that the gentlemen minded; they're his friends. It was their first performance in something like five years, and they wanted j. frede to open for them. They gave him an acoustic recording of theirs to manipulate for his show.

How anyone could've ever guessed what he was working with is beyond me-- according to j. frede, however, one audience member figured it out. The first thing I thought of was the soundtrack to some grainy and obscure foreign film. The sound kind of crept into the room; as it evolved, I envisioned some Tool video shit, like a marching army of creepy weather-beaten naked porcelain dolls, most of them missing limbs.

Eventually, the room sounded like the creaking inner-hull of a submarine. "Normally I would've gotten up and explained to people that the sound that I was using was the Denver Gentlemen's and given them an idea as to what was going on. I knew that that crowd, they were pretty sour about the fact that an electronic artist was opening for the Denver Gentlemen, so I was just like, whatever."

That crowd was lucky. During a show he put on at Chernobyl Tone Gallery-- a now-defunct art gallery/ performance space he owned and operated-- he locked the crowd inside, made sure there were no cops in attendance, and proceeded to construct a pipe bomb. Those in attendance got to check his progress using the diagram of a pipe bomb on the flyers they were holding in their trembling hands.

"People were running for the door when I got done. It really moved them and that was the whole point of the whole thing. I mean I was sweating bullets the whole time," j. frede said. "I like waking people up, making them have some sort of feelings, whether it's hate for me, or disgust, or anything, but people are so numb."

He didn't ever detonate the bomb; he thinks he might still have it somewhere. Appropriately located a few blocks east of the state capitol on Colfax-- the part of Colfax that most resembles the residual of nuclear fallout, complete with wandering C.H.U.D.S.-- Chernobyl gave j. frede and other electronic artists a place to set up camp and promote their art form.

Chernobyl also had ties to the Guerilla Artwarfare movement to which j. frede belongs. This movement involves everything from distributing upsetting propaganda to various bits of performance art to the bomb show-- getting art exposure by any means necessary. So how do you follow up the threat of critically wounding your audience and blowing off your own hands (in the name of art)? I have no idea, but I guess movies might be a good start.

Recording the sound of wind and trickling water in Telluride was part of j. frede's job as the audio curator for the Telluride International Experimental Cinema Exposition (T. I. E.) last year. Along with providing some of the ambient sounds between films, he scored a two-hour session of 20 silent films shown back to back. He received a video of the films just two days prior to the event. "I sat down and watched every film and just got a rough idea as to how I could manipulate the sound for each film." Then, using his equipment and some of the sounds he had recorded around town, he made soundtracks for the films while they played. "It was the most intense, stressful experience I've ever had musically ... afterwards, I sat for like 20 minutes and I was completely exhausted. Like physically exhausted."

With multiple releases, many on his own record label-- ritual document release-- you'd think j. frede would consider himself an accomplished musician. Not entirely the case. "I wouldn't call myself a musician, ever. I just refer to everything I do as sound. I would never say, 'Oh, I wrote a new song. ' I just feel like it's collections of sounds."

Denver, as it turns out, has a much better scene for experimental sound than many larger cities. Here, j. frede said shows featuring prominent experimental artists can yield nearly 200 people, but when he played with some pretty big names in electronic music in San Francisco, there weren't even 50 heads. "Touring the U. S. for electronic artists, unless they're working in the field of techno or it's just straight house music, is pretty much pointless."

Having toured extensively in Europe, j. frede has noticed several differences in people's attitudes towards his work abroad. "The field that I'm working in is vibrant over there ... everyone's really respectful and really into what's going on." The frustration of playing to many unreceptive crowds in America has, in part, impelled him to plan a move to Prague in October.

Not to say he'll leave Denver untouched-- he mentioned something about mounting speakers loaded with various prerecorded sounds in undisclosed locations downtown. Let's hope they're not also packed with gunpowder.

|

|

|

publication | Go-Go Magazine

date | January 2001

writer | Jenelise Pulliam

website | gogomagazine.com |

SONGS HEARD ROUND THE WORLD

The corporate industry has been ripping off artists for years; it's about time that the corporate industry gets ripped off," said J. Frede, local ambient noise musician and founder of Ritual Document Release, a distributor of not-so-corporate ambient recordings. Correspondence and business transactions for RDR are exclusively web-based. Frede also has tracks featured on MP3.com and RDR's website, http://www.ritualdocument.com/ The esoteric nature of Frede's music makes having access to an international audience instrumental in generating the size of a fan base needed to support J. Frede on his two previous European tours. The appeal for Frede is the idea of cyclical preservation and impersonal exchange of audio, not knowing or being able to accurately gauge who is listening to your music. His aspirations of Ritual Document someday being able to pay for itself and having wider distribution in the United States are almost guaranteed with the implementation of the web promoting for him.

|

|

|

publication | Westword

date | Feburary 2000

writer | Thomas Peake

website | Westword.com |

Welcome to the Terror Drone

Denver sound artist j.frede welcomes electronic experimenters, ambient minimalists and sonic terrorists into his life and his gallery.

For a public that ordinarily associates politics in music with can't-miss issues such as world hunger and rocking the vote, j.frede's theories about cultural hegemony can be as startling as his intense brand of electronic noise. "My whole political standpoint is about the idea of terrorists being victims trying to free themselves from their oppressors," explains the Denver soundscape artist, who was born James Frederick. "The world and the media really project terrorism as the exact opposite, as [terrorists] being the attackers and the aggressors," he says. "But in actuality, they're just in a bad situation, and they're doing everything they can to get out of it. It's a means to an end. And just their loyalty and their whole outlook and belief in everything they're doing is 100 percent stronger than most Americans can feel."

Among other things, j.frede is affiliated with the self-proclaimed Guerilla Artwarfare Movement -- a culture-jamming body that adheres to the notion that artists of all mediums must adopt an almost militaristic approach in order to compete for attention with consumerism and mass living. Yet neither j.frede nor his colleagues in the noise-as-art and art-as-war underground scenes advocate violence -- or a uniform ideology -- of any kind. In fact, the radical element that drives their work is all but concealed at performances and on recordings. However, upon closer inspection of j.frede's ambient electronics, industrial noise and droning beats -- with the now-defunct Chapter23; as a soloist at the Denver Atonal Festivals, which, until recently, emanated annually from the basement of the Chernobyl Tone Gallery at 508 East Colfax Avenue; and as Chernobyl's proprietor -- j.frede exhibits a dedication to his craft that bears resemblance to a fanatic's devotion to his cause. To some extent, he must: J.frede and his fellow sonic cacophonists are confirmed outsiders, for whom the entire realm of noise is as compelling or powerful as a structured, instrument-driven piece of music, if not more so.

And though j.frede is by no means the sole force behind Denver's curious affection for minimalist electronic noise-mongering, he deserves credit for establishing the Chernobyl gallery in April 1999, as a meeting place, performance space and art gallery for aesthetic outsiders. During its brief life as an out-of-nowhere art space on a thoroughfare more known for its thrift shops, crackheads and midget prostitutes, Chernobyl's visitors could never be too precise in their expectations of performances or events. The gallery was housed in a small storefront, where images of fallout, radiation and waste were visible to passersby more accustomed to the religious paintings, broken bed frames and book stacks found in adjacent businesses. Inside, j.frede and area co-conspirators like S.L.I.P., Asphyxia and New Mexico's Terrorstate -- all of whom performed at the 1999 Denver Atonal Festival in December -- regularly wreaked artistic havoc. In addition to the beats and scrapes of local electronicists, last year's roster featured everything from the melodramatic theatrics of Hoitoitoi to Vegetarianism, an installation/event that included raw meat, entrails and a cow's head.

Yet despite the fact that noise complaints from neighbors forced the gallery into a state of homelessness, j.frede and friends weren't driven underground; they were there to begin with. The gallery currently lacks a physical structure, but the impetus behind its formation is still very much in existence. "The whole point behind Chernobyl is to give artists that are doing much more minimal stuff and obscure sound a place -- more of a real place than, say, someone's house or a random venue or a cafe in the afternoon," explains j.frede. "It's actually developing a footing in the scene in Denver so these artists can have an actual space to do sound out of and build a following. So people know what to expect from Chernobyl and show up with that understanding."

Originally from the stark landscape of southern New Mexico, j.frede began performing six years ago, and though he's lived in San Francisco and toured the U.S. and Europe in recent years, Denver is, emphatically, home. "There's nowhere else that I know of in the country that's got any kind of live ambient scene going on," he says. "So Denver's definitely the place with the biggest draw. We had between 75 and 150 people at some of the festivals and shows we've thrown. That's pretty good for this type of sound."

And Denver's scene is one that doesn't just think locally. J.frede has hosted or organized performances by Nmperign, a free improv sax/trumpet duo from Boston; the ethnic industrial beats of Macedonia's Kismet; San Francisco-based solo contrabassist Morgan Guberman; and Japanese noise fiends MSBR. For the spring and summer of 2000, j.frede confirms that Chernobyl -- wherever it may be -- will host concerts by two legendary enigmatic British groups, Zoviet France and the Hafler Trio, as well as Finland's Pan Sonic.

Though j.frede himself cites the last two as musical influences along with Experimental Audio Research, getting a handle on his pedigree is not easy. "The abrasion behind some of the sound I do could be looked at as audio terrorism," he says of his sound stylings, and it's an apt description. His recent recordings are alternately assaultive and overhwhelming, a sort of aural manifesto that variously suggests the arid, consolatory trances and drones of Robert Rich or Nurse With Wound, thunderous deconstructions à la C.W. Vrtacek or C.M. Von Hausswolf, and the unpredictable, piercing frequencies generated by Illusion of Safety, Voice Crack or Gastr del Sol. On top of it all, slowly roiling low-end beats animate certain passages of j.frede's work. His artistic range might be best explained by more important, earlier influences that encourage constant change -- artists such as John Cage, composer and pioneer of prepared-piano techniques and aleatoric music, and La Monte Young, minimalist composer and designer of theatrical environments for sound and light. "The prepared-piano stuff John Cage was doing in the '50s is just mind-blowing," j.frede says. "He would have entire concert halls full of people in tuxedos to see certain pianists, and he would have the pianists go out and just sit in silence. Everyone's ears would be piqued, waiting for him to start playing...Then he would come out and explain to everyone that that was his ambient sound for the evening -- everyone shuffling and clearing throats and whispering."

Cage's famous composition, 4'33", requires neither instruments nor actual performance. j.frede can identify. "I don't play any instruments," he explains. "I play with instruments." His toy chest consists of synthesizers, a Speak & Spell game and a host of other black boxes. And Cage himself would no doubt be proud of j.frede's creativity in using a variety of sound sources to form textural, sometimes rhythmic walls -- or curtains -- of noise. His live performances have included The Acoustics of Metal, a short play period with springs, bowls, balls and sheets, and The Acoustics of Glass, which uses water, contact mikes and thick glass plates to generate contrasting tones. On other occasions, j.frede has made rapid sonic detours from material performed earlier in the same evening and from environmental recordings made in the cities that he's toured.

The success of all of these schemes is heavily affected by both sound-system quality and audience vibe. When he encountered a blown PA at a warehouse show last year, for example, j.frede set the dials to destroy and started unplugging. Instead of an avant dance set with JudeS, his partner in the group Mono, the audience received a brief, satisfying and ferocious dose of feedback.

Recent setbacks -- most notably, Chernobyl's closure -- haven't caused a slowdown of j.frede's output or of his efforts as a live performer. His seven-inch EP, Isolate, released on his Ritual Document Release label in January, exhibits two short, abstract slabs of rumbling drones and atmospheric clang. But even though the package is exquisite and the locked grooves wondrous, seven-inch vinyl is a format more suited to the pop singles for which it was invented. More promising, then, is the forthcoming Denver Atonal Festival double-CD set, a live recording of the event's highlights. For those who missed the performances under the dim red lights at Chernobyl in December, this set will present the affected sitars of Jessica Ivers-Frederick and David, the mounting samples and fractal spawn of Terrorstate, the Morse codes and low-frequency quiet noise of JudeS's S.L.I.P., and half a dozen more performances of note. Also in the works from j.frede are another seven-inch, a split twelve-inch LP with local group Annik, the Eremiophobia CD and the Plainscape Recordings CD. (Samples of j.frede's sounds can be found at www.mp3.com/jfrede and www.geocities.com/Area51/5383/chapter23/.)

And while he and colleagues search for a new space for Chernobyl, j.frede's found other performance venues, unlikely as they may be. The first in a series of quieter ambient sessions featured j.frede and Patrick Birch at the downtown Barnes & Noble bookstore in early January. An odd setting, certainly, but a successful one nonetheless. And on Friday evenings, j.frede holds forth as DJ at the Snake Pit. This month, he'll open an audio installation at GOOG, a gallery run by an architectural firm. The project, which will demonstrate j.frede's recently acquired 3-D sound system, will use samples captured in the firm's metal shop as the sole sound source.

J.frede concedes that the old Chernobyl space was more conducive to his endeavors. Because even when the technology is a go, the setting can still bring down a show. "It's not really something everyone will understand," he says of a recent performance at Seven South. "I asked for people to be respectful and be quiet at least until I got started, [but] people started heckling me, and I just don't accept that well." He exchanged a few words with a belligerent patron who he says was more accustomed to the musical paradigms offered by Whitesnake; then j.frede, not a towering figure by any means, courageously or foolishly confronted the heckler. Later, about thirty seconds into the set, j.frede overturned the tables holding all of his equipment, causing disbelief among those in the audience who could appreciate the dollar value of the electronics that crashed to the floor.

As with terrorist behavior, a certain David-versus-Goliath dynamic may have been at work that night (although some might argue it's a Napoleon complex). Whatever the case, j.frede's intensity and aesthetic should prove uncompromising rather than dysfunctional, ultimately a benefit to the avatars of underground art in Denver.

"A big part of it was that I had been used to playing Chernobyl, where people were there because they wanted to hear the music and they wanted to be part of the atmosphere. Obviously, at Seven South, they were just there to drink and whatever," j.frede continues. "I don't take well to heckling, especially when I'm trying to present myself and I'm in a vulnerable situation. I just counterattack."

|

|